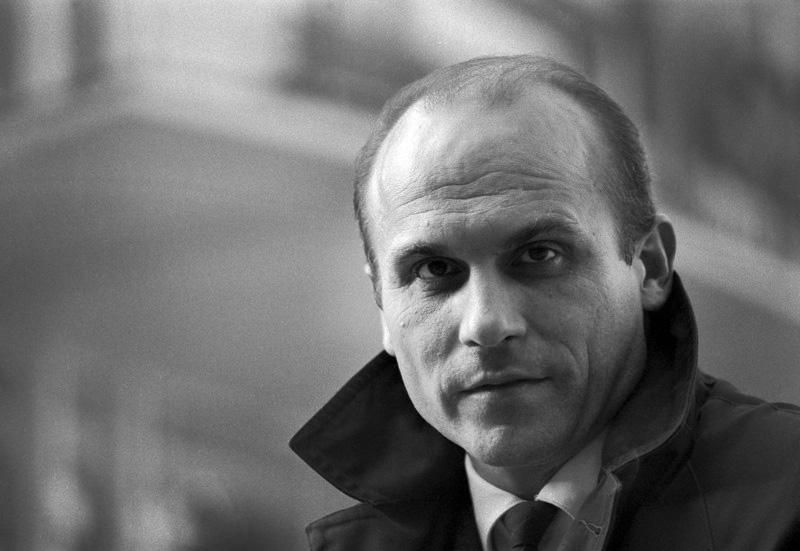

44. Ryszard Kapuściński

“There are two kinds of global maps printed in the world.” -Ryszard Kapuściński, translated by Klara Glowczewska

1.

When I was eight, I was into geography.

I studied atlases, memorized capitals, had a special thing for flags. A

developing tendency toward obsessiveness was showing itself for the first time,

albeit in a gentle childlike manner that was easily encouraged, and this

encouragement must have extended to the day camp I was attending. I don’t

remember the details, but I do know that, sometime during that summer, I ended

up painting my very own map. The counselors must have provided me with a

canvas (a circular grainy thing about 3 feet in diameter) and paints (blue,

white, and black) and set me loose because the proof is still there to see.

Over three decades later, the flattened globe remains tacked to the wood-paneled

wall of my parents’ basement.

My map was

full of a child’s inevitable errors, but these were mostly errors of scale: South

America squeezed to a few inches in width because I didn’t leave enough room

for it, Madagascar the size of the rest of Africa because I overestimated its

importance. Drawing on my closely hoarded knowledge of world geography (and maybe

aided by a few sneak peaks at the atlas), I managed to get most of the

landmasses in the correct places, if not in the right sizes. The U.S. and

Canada sat neatly in the center of the map with Greenland to their right.

Continuing along, Europe and Africa came next, each in its proper place. Beyond

them lay Asia and the Soviet Union, but they quickly ran out of room. Split in

two, they were only able to continue their impressive sprawl on the far left

side of the map.

2.

Negativland’s 1987 audio collage “Time Zones” is built around an exchange between a radio host (likely conservative

KABC personality Ray Briem) and a caller named Glen. The subject of their

conversation, which is repeatedly chopped up and remixed by the group, is the

question of Soviet power. While the caller tries to make a case for the global

force of the United States, the host brings him up short with a pointed

question: “Do you know how many times zones there are in the Soviet Union?”

When Glen says he doesn’t, the host sets him straight. In contrast to the mere

four time zones in the U.S., the Soviet Union has a whopping eleven.

The

conversation is typical Cold War fearmongering, but in Negativland’s hands, it

takes on an anxious resonance that works both at cross-purposes to the warnings of the Ray

Briems of the world and, perhaps inadvertently, in their support. Negativland,

a musical outfit known for their sound collages, their anti-consumerist ethos,

and their practice of “culture jamming” (whereby they turn the world of

mainstream media against itself through recontextualization and art-pranks),

slice and dice this radio exchange and insert various additional sounds,

including the presence throughout of an ominous round of bells. The bells, echoing

in a repetitive up-and-down pattern, combine with the starched tone of warning

in the host’s voice to create a sense of impending doom. In Negativland’s

détournement, this doom may attach itself to and indict the right-wing cold

warriors of the time, but it also serves to give their words added weight. When

poor Glen, absorbing the host’s lesson, says that “The Soviet Union’s the whole

half side of the world and we’re just… one little tenth of the globe,” he doesn’t

sound so much like a benighted rube (even if his measurements are a bit off) as

a bringer of very real, and very terrifying, news.

3.

According to Polish journalist Ryszard

Kapuściński,

Russian maps from the Cold War followed a completely different pattern from

their U.S. counterparts, a fact that is as instructive as it is unsurprising.

Documenting the dissolution of the Soviet Union in his book Imperium, Kapuściński

notes that while American maps were designed to protect children from being

scared of the U.S.S.R.’s immense bulk by splitting the empire in two, Soviet

maps reversed the trend. In these Moscow-based charts, the middle spot is

reserved for the Soviet Union “which is so big that it overwhelms us with its

expanse; America, on the other hand, is cut in half and placed discreetly at

both ends so that the Russian child will not think: My God! How large this

America is!”

For Kapuściński,

the two maps “have been shaping two different visions of the world for

generations,” and this spatial understanding is key to unlocking the psychology

of the Russian citizen (and, no doubt, the American one, too.) Wherever Kapuściński travels

throughout the Soviet Union, he sees the Russia-centric map for sale and this

leads him to reflect on the ways that the sheer bulk of the country and its

corresponding imperialist might serve as both a source of pride and a “kind of

visual recompense” for the Soviet citizens’ otherwise difficult lives. This begets

what Kapuściński calls the “imperial scale of thinking,” endemic to the

ruling class but shared by a good chunk of the general citizenry as well. In this mindset,

local concerns barely register and only the ongoing continuation of the empire,

the Imperium, is of any importance. Even for many of the most impoverished subjects, this proves

to be the case: Kapuściński cites the example of old women leaving

breadlines to protest the U.S.S.R.’s right to the disputed Kuril Islands. “Between

the Russian and his Imperium a strong and vital symbiosis exists,” he concludes.

As in 19th century America, so in the Soviet Union, even as it

teeters on the brink of dissolution. In the land of eleven time zones, geography

becomes destiny. It requires only the concrete visualization that comes with a

map to stir the soul of a populace.

Comments

Post a Comment