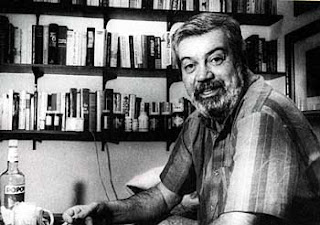

42. Frederick Exley

“Edmund Wilson, seventy-seven, one of the great men of the twentieth century, died this day at six-thirty this morning in this old stone house at Talcotville.” -Frederick Exley

Among those works whose potential

resemblance to his own causes Baker some fretting is Frederick Exley’s Pages

from a Cold Island. The second book in Exley’s loose trilogy of

autobiographical novels (Exley insists in a note to the reader that the book is

nonfiction; his publisher classifies it as fiction), Pages deals with,

along with many other things, the death of legendary critic Edmund Wilson.

Although, in revisiting Exley’s book, Baker worries that, like his own effort,

it begins with the death of an author (in Baker’s case not Updike but Donald

Barthelme), he quickly reassures himself by noting that his work will then move

in a very different direction from Exley’s. “That is just where you are

trying to take the next step,” Baker tells himself, “since Exley then occupies

himself with talking to Edmund Wilson’s daughter and rereading his fiction,

whereas you leave Barthelme behind and move to someone [Updike] whose survivors

aren’t yet hugely important, because the man lives still!” (U and I was

published in 1991.)

In fact, Baker needn’t have

worried. Beyond the superficial preoccupation with another writer, the two

works resemble each other very little, to the point where it’s not clear

whether Exley’s book even belongs in the mini-canon that Baker has assembled.

For one thing, while Exley proclaims his high opinion of Wilson throughout (“one

of the great men of the twentieth century”), he never tells us why the critic

is of particular significance to him. This grappling with an older author’s

legacy and its personal import for the writer is the sine qua non of the

mini-genre and it’s not really present in Exley. Then, too, if one of the

pleasures of the meta-essay is getting the author’s personal—and hopefully

provocative—take on the relative merits of another author’s bibliography, Exley

gives us very little of this, either. He downgrades Wilson’s late-career opus Patriotic Gore, a book whose crotchety weirdness matches its ambitions and makes for

thrilling, if frustrating reading, and he quotes largely from Wilson’s

end-of-life memoir, Upstate, which he considers a minor work, and, after

that, there’s not a whole lot else. His most sustained critical engagement

comes early on when he re-reads Wilson’s novel Memoirs of Hecate County,

which, while Wilson’s own favorite among his books, has not come down as a

great favorite, and which Exley finds more than a little silly.

Instead, and this is like U and

I, although in a very different way, Pages from a Cold Island is

about the struggle to write the book we’re reading. In Exley’s case, it’s about

the effort to put together enough interesting material to fill it out. Exley

totes around a 400-page manuscript that he’s been working on for years, but

admits that “it didn’t at all work on that heady level I desperately yearned

for it to work” and so he realizes that it requires not only massive amounts of

excision but plenty of new material as well. This new material comes in the

form of previously published magazine pieces which detail the author’s efforts

to interview Gloria Steinem and his tracking down of Edmund Wilson’s secretary

and daughter, essays which Exley then interpolates into the text. It’s a

hodgepodge book and all the better for it, as this appealingly shaggy quality

jibes with Exley’s ad hoc, alcoholic’s sensibility.

Of course, some of the material is

more successful than other and while the book begins with Wilson’s death, it

doesn’t return in earnest to the critic until the novel’s back half. Exley’s a

depressive who writes exuberant prose but these chapters are among the more restrained

and thus duller things in the book, probably as a result of the journalistic

requirements imposed by the Atlantic, where they first appeared. Far

more appealing are the scenes set among the down-and-outs of Singer Island,

Florida, where Exley lives, drinks (heavily), and mingles with the locals until

creeping gentrification (the book’s action unfolds in the early 1970s) begins

to force what was already a transient population out. Exley’s best talents are

for his vivid evocations of the places he calls home (Singer Island here;

Watertown, New York in his celebrated first book, A Fan’s Notes), and Pages

from a Cold Island lingers most vividly in the mind not as a reckoning with

the ambivalent influence of an older writer, but as a portrait of a man adrift

in a setting that suits that lack of direction just fine. For all Exley’s fretting,

this focus suits his book just fine, too.

Comments

Post a Comment