39. Nicholson Baker

“We could just have lunch at the Friendly Toast.” -Nicholson Baker

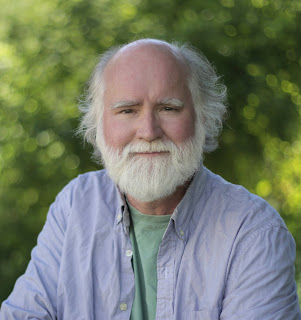

One of the best things I learned this

last year is that Nicholson Baker likes to write at Friendly’s. (Or at least he

used to back before most of the chain restaurant’s locations shut down.)

There’s something about the image of the novelist/essayist/part-time historian

with his white beard and his flannel button-down shirts tucked away at the

corner booth at his local Maine location, scribbling down his trademark

left-of-center observations between bites of a cheeseburger, that comforts and

delights. A lot of the appeal has to do with the everyman image it conjures up.

Writing isn’t that serious of a business, this image says. It need not be

something squeezed out in monastic solitude by a malnourished true believer, it

can be done just as easily by an affable late middle-aged man at a casual

dining restaurant, merrily jotting down his thoughts before the lunch rush hits.

Of course, for all the zaniness of

his books, writing is a very serious business for Baker. His earliest volumes,

the novels Mezzanine, from 1988, and 1990’s Room Temperature, announced

him as a miniaturist, wryly attuned to the tiny details that constitute the

stuff of daily life as they flit across the minds of his narrators. These books

made the case for serious attention, a renewed concentration on the world in

front of us, even as they kept their focus narrow. Subsequent projects, though,

would expand Baker’s interests to the wider world, and particularly to its

larger political questions. In both nonfiction books like Human Smoke,

in which Baker carefully marshals evidence to present a revisionist take on

World War II, and novels like Checkpoint, which consists of a running

dialogue between its two characters about whether or not to assassinate George

W. Bush, Baker turned his attention in the 2000s to political questions, serving

up provocative theses and offering a genuine challenge to received historical wisdom.

Through it all, though, Baker kept

returning to his earlier mode as well, publishing novels of witty, small-scale

contemplation in between his more outward-looking volumes, as when he chased

2008’s Human Smoke with the far less sober The Anthologist the

following year. That novel follows sad-sack middle-aged poet Paul Chowder as he

avoids writing the introduction to a new anthology of rhymed verse that is already

considerably overdue. Along the way, he muses on his failures, offers an

iconoclastic reading of the history of poetry, and lets us in on the day-to-day

habits and activities that constitute his life. It’s a largely light-hearted

affair, one that, though not without plenty to say on the subject of both 50-something

malaise and the serious business of versifying, has fun coining witticisms, experimenting

with voice, and poking its nose at the literary establishment. It’s exactly the

type of book it’s easy to imagine Baker banging out at his local Friendly’s.

So, too, is its follow up, 2013’s Traveling Sprinkler, which continues the adventures of the now slightly less hapless

Chowder and from which the above citation is taken. (The fictional Friendly

Toast, if anything, sounds even more inviting than the chain restaurant whose

name it recalls.) Having finally turned in his introduction at the end of The

Anthologist, Chowder, in the newer book, switches his attention to

song-writing, beat-making, and trying to win back his ex-girlfriend. As before,

his wandering thoughts fill the spaces in between, but this time there’s a

wrinkle: among the narrator’s musings is some decidedly political content. He

gives serious thought to the brutal casualties of drone strikes and the

murderous history of the C.I.A. as he tries to steer his newfound songwriting

ambition in the direction of protest music.

It’s a

largely successful mix that Baker achieves, as his narrator pulls himself out

of the previous novel’s funk by attempting to engage with the wider world in a

way he hadn’t before, melding small-scale political action (or at least

thought) with personal development. But, still, what I like best about the book

are the smaller moments, the scenes of Chowder interacting with his immediate

surroundings. The narrator’s life in his small New Hampshire city is

self-contained and cozy and, perhaps because the town I live in is a little too

self-contained and cozy and, in any event, is largely shut down due to

quarantine, my keenest pleasure in reading Traveling Sprinkler is to

project myself into Chowder’s world. At one point in the book, he considers

going to a Mexican restaurant at a strip mall and eating dinner at the bar. This

sounds as good as lunch at Friendly’s—or better, given the margaritas—and when

he decides against it, it feels suddenly like a colossal miscalculation on his

part. The Friendly’s that I grew up eating at became a mattress store about

five years ago and the Mexican restaurant where I used to have dinner at the

bar closed two years back, the building still without a tenant. Now, many more

restaurants and businesses have shut down and still many more are likely to do

so this year. Paul Chowder—and Nicholson Baker when he was creating Paul

Chowder—lived in another time, even if it wasn’t that long ago. I hope they

enjoyed the nachos and cheeseburgers while they could.

Comments

Post a Comment