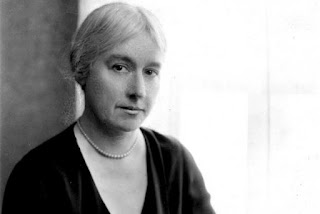

31. Constance Rourke

“Indeed the story of Rip Van Winkle has never been

finished, and still awaits a final imaginative re-creation.” -Constance Rourke

Where I

live, Rip Van Winkle is everywhere. To get to my Hudson Valley town, I drive

across the Rip Van Winkle Bridge and am greeted by a sign, depicting a

silhouetted image of the legendary napper, proclaiming this the “Land of Rip

Van Winkle.” As I drive downtown, I pass a wood-carved statue of Rip. Popping

into a local coffee shop, I can buy coffee allegedly so strong it can “Awaken

Rip.” Driving further, I might pass the bare-bones Rip Van Winkle Motor Lodge

en route to grab a beer at the Rip Van Winkle Brewery. If I feel like roughing

it, I can stay at the Rip Van Winkle Campgrounds; if I want to buy a house, I

can turn to Rip Van Winkle Realty.

Part

marketing strategy, part source of local pride, this appropriation of

Washington Irving’s 1819 story by a wide array of businesses and local boosters

is not a new development. During the 19th century, when the Rip

legend spun off from the original story and became the subject of numerous

popular plays, the mania for naming things after the sleepy Dutchman was as

pronounced as it is today, used as it were, at least in part, to lure tourists to the area.

Although Irving’s story takes place in an unnamed village at the foot of the

“Kaatskill” Mountains, “a little village of great antiquity,” one that is

unlikely to be based on the town where I live (the author himself plays it coy: “I can give you no other information concerning the localities of the

story 'Rip Van Winkle,' than is to be gathered from the manuscript,” he wrote in 1858), it hasn’t stopped the municipality’s

identification with Irving’s most enduring creation.

This

seems especially true in recent years when both tourism and second-home buying

have reached new levels of excess, with city folk looking for a weekend getaway

turning to the area and its endless proliferation of scenic locales, boutique

shopping experiences, and Airbnb rentals to provide them with a perfectly

curated weekend. Enter Rip to help sell them a quaint, charming view of the

region. And in recent months, those city dwellers lucky enough to secure a

second home or an ongoing Airbnb appointment in the region that real estate

interests like to dub the Camptons have beat a neat retreat upstate, enjoying a

leisurely vacation from the COVID-ravaged city. Although I only moved upstate

(albeit full-time) less than two years ago, I still work up a righteous anger

every time I see an obvious city-dweller walking around town. After all, the

Land of Rip Van Winkle may be rich in history and charm but it is not so

abundant in hospital beds. My county is without a hospital at all and although

there is one located just across the river, it can accommodate only 192 admitted

patients.

*****

In her

classic 1931 study of American popular culture, literature, and identity, American Humor: A Study of the National Character, Constance Rourke reflects on the

enduring popularity of Rip Van Winkle throughout the 19th century. While, as Rourke explains, many people have considered the period from the late

1860s through the 1880s “an arid waste so far as creative expression is

concerned,” those years were “in fact alive with a consistent purpose. It was

as if a people were trying to bury itself in its deeper resources.” These

resources were the primitive, archetypal figures of earlier American myth and

no character served this purpose better than Irving’s endlessly endearing

slugabed. Although Rourke notes that throughout the middle of the 19th

century, some theatrical version or other of Rip was almost always to be seen

on the stage, the “small story [growing] through fifty or sixty years in a

dozen experimental versions,” it was the version premiered by the actor Joseph

Jefferson in 1865 which properly inaugurated a new vogue for the character.

Following a successful Broadway run, Jefferson continued to portray Rip for

over forty years.

But what

was it specifically about Van Winkle that created such an enthusiasm? According

to Rourke, it was only partly due to Jefferson’s portrayal and only partly due

to the “beauty of the local fable.” She offers another, more cogent explanation:

“The meaning of [the] fable met the current feeling by picturing the sudden

gulf of years.” Although Rip’s awakening is undoubtedly comic, the comic is

often, as Rourke insists throughout her book, tied up with deep reservoirs of

emotion, and for a people living in the aftermath of the cataclysm of the Civil

War, the character’s sudden emergence into a new country that didn’t exist when

he fell asleep must surely have resonated beyond any questions of the local

picturesque.

Rourke’s

point here is that American popular culture (as well as high literature) tends

to draw on the same set of American archetypes and characters but adopts them

to its own specific circumstances. Thus Irving’s Catskill tale morphs

throughout the 19th century and continues to morph, awaiting that

“final re-creation.” As we suffer through our own sudden gulf of years, thrust unexpectedly

into a world that seems alien and terrifying and not at all comic, the old Rip

Van Winkle legend is both freshly relevant and insufficient for our purposes.

The institutions we took for granted are no longer holding and the well-to-do who

have retreated northward, drawn by the promise of an enchanted, mythical land,

are the only ones sure to survive. Rip Van Winkle may address our sense of

dislocation, but if he is to achieve a true final re-creation, he must speak to

something more than the gulf of years or to the false promises of an idyllic

retreat. For a new Rip to emerge, an altogether new form of awakening is required.

Comments

Post a Comment