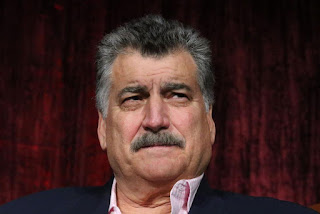

6. Keith Hernandez

“Eat

your heart out, UPS and FedEx: when it comes to logistics and moving assets

around, Major League Baseball destroys you.” -Keith Hernandez

Keith Hernandez is, to

put it mildly, a little old school. Watch any Mets telecast and this becomes apparent

pretty quickly. The former first baseman turned television analyst has little

taste for the changes that have visited the contemporary game, huffing in

disgust at such recent innovations as the shift or instant replay. Sometimes,

this old school attitude extends to political and social commentary and the

results can get Hernandez in trouble. In 2006, he famously decried the presence

of a female massage therapist in the San Diego Padres dugout, leading to much

criticism and, later, an apology from Hernandez. In his new memoir I’m Keith

Hernandez, where he expounds at somewhat unsatisfying length on his

feelings about the incident (it all goes back to his self-consciousness about

boil scars on his butt), he describes himself as follows: “a member of an older

generation with somewhat conservative political and social views that aren’t

radical but perhaps not mainstream either.”

These views (in addition

to his occasional sexism, he says things like “the Spanish Empire was great”

and Carly Fiorina is “smart… Margaret Thatcheresque”), make it hard to embrace

Hernandez who seems to revel in his role as dinosaur. But those same dinosaur

attitudes that have no place in civilized discourse are, when applied to the currently

troubled sport he’s dedicated his life to, in many ways, quite necessary. And, further,

for all their surface level conservatism, his takes on 21st century

baseball, were he able to follow these lines of thought out into extra-athletic

territory, might lead to a far more enlightened world view than the one that we

know him to keep. (But this divide is hardly unique to Hernandez; many

ballplayers hold to staunchly right-wing politics, except when it comes to

strong support for the union that they happen to belong to.)

Hernandez begins chapter

11 of his book with a cheeky, intentionally exaggerated description of the fate

that might befall a struggling young minor league baseball player in today’s

game. Whereas when he was scuffling at Double A in 1973, his general manager

understood it was a question of confidence and, rather than demoting him, sent

him up the ranks to Triple A, today’s ballplayer would stand no chance. Subjected

to the management of a computer whiz kid who’s been put in charge of the front

office and relies entirely on algorithms rather than any innate understanding

of the game, the young player would be demoted, made to feel he’s living under

a microscope, panic, and eventually play himself out of a job. This is what

happens when athletes are seen simply as “assets” that exist to be constantly

“moved around” by management.

This management strategy

is just one of the problems with Baseball According to Keith. But it’s not just

Hernandez that sees problems. The sport is widely understood to be in crisis

mode, largely the product of a style of play—all strike outs and home runs—that

is not only deadly dull but makes the game take far longer to unfold than

anyone would like. Commissioner Rob Manfred’s solutions, such as instituting

pitch clocks, are rightfully ridiculed by Hernandez, who understands that the real

problem lies elsewhere.

But Hernandez saves his biggest

critique for the algorithmic systems that have come to dominate the management

of the game. (In this he’s not alone. Last year, former outfielder Jayson Werth

blasted the “super nerds” running baseball front offices, saying “it’s to the

point where you just put computers out there… just put them out there and let

them play.”) What Hernandez understands is that this drive towards a

dehumanizing efficiency is killing baseball. What he perhaps doesn’t

understand: that this drive towards a dehumanizing efficiency is killing the

world. It’s easy enough to see the sports world as self-contained, but what

happens in baseball doesn’t remain safely contained within its specialized

borders. Hernandez is a smart guy (or so everyone in the book keeps telling

him.) Surely he can see that the same instinct that compels baseball GMs to

reduce players to data sets fuels so much that goes on in the world beyond the

diamond, as exemplified by the massive control exerted on our access to

information by tech giants like Google and Amazon. If we follow the lessons we

learn from sports out into the wider world, we might be surprised at the

conclusions we reach. For the sometimes lovable curmudgeon known as Keith

Hernandez, it might just prove to be a revelation.

Comments

Post a Comment